Lense–Thirring precession

In general relativity, Lense–Thirring precession or the Lense–Thirring effect (named after Josef Lense and Hans Thirring) is a relativistic correction to the precession of a gyroscope near a large rotating mass such as the Earth. It is a gravitomagnetic frame-dragging effect. According to a recent historical analysis by Pfister,[1] the effect should be renamed as Einstein-Thirring-Lense effect. It is a prediction of general relativity consisting of secular precessions of the longitude of the ascending node and the argument of pericenter of a test particle freely orbiting a central spinning mass endowed with angular momentum  .

.

The difference between de Sitter precession and the Lense–Thirring effect is that the de Sitter effect is due simply to the presence of a central mass, whereas the Lense–Thirring effect is due to the rotation of the central mass. The total precession is calculated by combining the de Sitter precession with the Lense–Thirring precession.

Contents |

Derivation

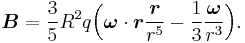

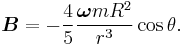

Before we can calculate this we want to find the gravitomagnetic field. The gravitomagnetic field in the equatorial plane of a rotating star:

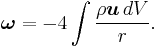

If we use then:

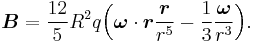

We get:

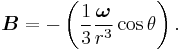

When we look at Foucault's pendulum we only have to take the perpendicular-component to the Earth's surface. This means the first part of the equation cancels, where the radius  equals

equals  and

and  is the latitude:

is the latitude:

The absolute value of this would then be:

This is the gravitomagnetic field. We know there is a strong relation between the angular velocity in the local inertial system,  , and the gravitomagnetic field:

, and the gravitomagnetic field:

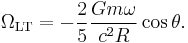

Therefore the Earth introduces a precession on all gyroscopes in a stationary system surrounding the Earth. This precession is called the Lense–Thirring precession with a magnitude:

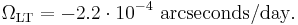

As an example the latitude of the city of Nijmegen in the Netherlands is used for reference. This latitude gives a value for the Lense–Thirring precession of:

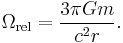

The total relativistic precessions on Earth is given by the sum of the De Sitter precession and the Lense–Thirring precession. This can be calculated by:

At this rate a Foucault pendulum would have to oscillate for more than 16000 years to precede 1 degree.

Intuitive explanation

According to Newtonian mechanics, a body rotates or does not rotate relative to an absolute space. This absolute space is fixed. Ernst Mach criticized this idea, and proposed that the absolute space does not exist, it should be defined by the bodies that exist in the universe. So when we see a body rotating it would be rotating relative to the rest of the bodies in the universe. This idea that the bodies define in some way the reference frames became incarnated in the relativistic theory of gravitation, proposed by Albert Einstein in 1915. As a consequence, the rotation of nearby objects affects the rotation of other objects. This is the Lense–Thirring effect.

As an example of the Lense–Thirring effect consider the following:

Think of a satellite rotating around the Earth. According to Newtonian Mechanics, if there are no external forces applied to the satellite but the gravitation force exerted by the Earth, it will keep rotating in the same plane forever (this will be the case whether the Earth rotates around its axis or not). With General Relativity, we find that the rotation of the Earth exerts a force to the satellite, so that the rotation plane of the satellite precesses, at a very small rate, in the same direction as the rotation of the Earth.

References

- ^ Pfister, H. (November 2007). "On the history of the so-called Lense–Thirring effect". General Relativity and Gravitation 39 (11): 1735–1748. Bibcode 2007GReGr..39.1735P. doi:10.1007/s10714-007-0521-4.

External links

- (German) explanation of Thirring-Lense effect Has pictures for the satellite example.